Growth charts — WHO standards versus India crafted

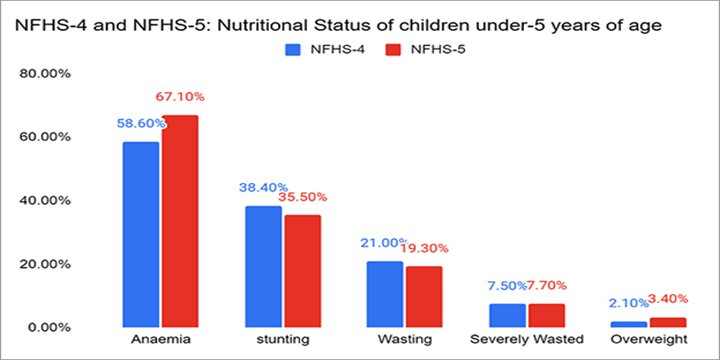

Context- Child undernutrition is a long-standing issue in India, with numerous factors contributing to it. These include dietary intake, diversity in diet, health conditions, sanitation, the status of women, and the broader context of poverty. The most prevalent methods for measuring childhood undernutrition are anthropometric standards, such as height-for-age (indicating chronic undernutrition or stunting) and weight-for-height (indicating acute undernutrition or wasting).

Regular monitoring of these measures is crucial for assessing progress. Like many other countries, India uses the World Health Organization (WHO) Growth Standards, which are globally accepted, to gauge malnutrition. However, the application of these growth standards in India has sparked a growing debate on several issues.

On using the MGRS as the base

- The World Health Organization (WHO) standards are derived from a Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS) conducted between 1997 and 2003 in six countries, including Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman, and the United States.

- The study aimed to establish the growth pattern of children from birth to five years who were not exposed to any known environmental deficiencies. The previously used references (WHO-National Center for Health Statistics references) were based solely on children from the U.S., many of whom were formula-fed instead of breastfed.

- The MGRS adopted a prescriptive approach, intending to set growth ‘standards’ (how children should grow in a healthy environment) rather than growth ‘references’ (how children in the reference group grow).

- The Indian sample in the MGRS was selected from privileged households in South Delhi, where children met all the study’s eligibility criteria, including a ‘favorable’ growth environment, breastfeeding, and non-smoking mothers.

- Some researchers analyzing data from other Indian surveys suggest that these standards may overestimate undernutrition.

- However, such comparisons would only be valid if the datasets could provide samples that meet all the MGRS-defined criteria for a favorable growth environment.

- Given the high levels of inequality and underrepresentation of the wealthy in these datasets, it is challenging to find an adequate number of equivalent samples in large-scale Indian surveys.

- For example, only 12.7% of children (aged six-23 months) in the highest quintile households in the National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-5 (2019-21) meet the WHO-defined ‘minimum acceptable diet’ requirements.

- While nearly all mothers in the MGRS sample had more than 15 years of education (in 2000-01), only 54.7% of women in NFHS-5 had completed 12 or more years of schooling.

- Comparisons could also be misleading because the WHO-MGRS study norms differed significantly from these prevalence studies.

- For instance, the MGRS included a counseling component to ensure appropriate feeding practices, which is conspicuously absent in the NFHS or Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey.

- Once it is understood that the MGRS sample was intended for setting prescriptive standards, most sampling concerns are addressed.

- Further issues raised concerning the MGRS methodology, such as data pooling from different countries, have been extensively discussed in the study reports.

Genetic growth, other concerns

- A significant concern regarding the use of MGRS standards is the potential genetic growth differences between Indians and other populations, and the impact of maternal height on child growth. Maternal height, at an individual level, is an undeniable and unchangeable factor influencing a child’s growth.

- This raises the question of how much growth improvement can be achieved in a single generation. However, low average maternal heights are a reflection of the intergenerational transmission of poverty and the disadvantaged status of women, indicating an environment of deprivation.

- An appropriate indicator of such an environment, like stunting, should capture this deprivation.

- While the question of whether the standard is too flexible to be useful remains relevant, considering the issues of maternal heights and genetic potential, it’s worth noting that several countries with similar or even worse economic conditions, including those in South Asia, have shown greater improvements in stunting prevalence using the same WHO-MGRS standards.

- Regional differences within India, in terms of stunting prevalence and increases in adult heights, suggest that some states like Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala are achieving faster reductions than others.

- It’s also important to consider that gene pools can shift at the population level with socio-economic development, as evidenced by the increasing average heights in countries like Japan, challenging the notion of fixed genetic potential.

- Another serious concern is the potential for misdiagnosis due to excessively high standards, which could lead to overfeeding of misclassified children under government programs designed to address undernutrition, resulting in an increase in overweight and obesity.

- This is a concern, especially considering the rising burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in India. However, given the dietary gaps in children’s diets and the poor coverage of schemes like mid-day meals and supplementary nutrition in anganwadis, these fears seem largely unfounded.

- The quality of meals under these schemes needs to be improved to ensure they are not overly reliant on cereals, include all nutrients, and contribute to dietary diversity. Urgent action is needed on recommendations such as including eggs in children’s meals and pulses in the Public Distribution System.

- It’s widely understood that improving diets, along with other interventions like better sanitation, access to healthcare, childcare services, etc., are necessary for better nutritional outcomes.

- Undoubtedly, there are numerous gaps to address in the more distant determinants of stunting, primarily livelihoods and poverty, access to education, and women’s empowerment. These objectives are inseparably connected to the country’s overall development and the equitable distribution of resources.

- Their manifestation in anthropometric indicators only underscores the significance of these summary indicators. It’s important to recognize that each child grows in a unique way, and trained child health professionals, such as treating physicians, can make judgement calls when interpreting growth charts for individual children under their care.

- These standards are primarily used to understand population trends. Using the correct standards is also crucial for international comparisons and intra-country trends, an advantage that would be lost with any new country-specific standard.

Way Forward-

The Indian Council of Medical Research has formed a committee to review India’s growth references. This committee has reportedly suggested a comprehensive nationwide study to investigate child growth, with the aim of creating national growth charts if needed. However, while gathering more accurate data on child growth is a positive step — especially considering our ambitious goal of achieving development for everyone by 2047 — it seems reasonable to adhere to the high yet attainable standards proposed by the WHO-MGRS.

Source- Indian Express